Numéro: When did you start writing Consumed?

David Cronenberg: It started as a screenplay around 2008. There was the idea of this French philosophical couple, a sort of naïve North American journalist couple and the apparent murder of the wife from the French philosophical couple, which the journalists had decided they should investigate. But at a certain point I couldn’t continue – sometimes something dies, you just don’t know why. In retrospect I may have romanticized it, but I felt I couldn’t have fulfilled the promise of the premise in movie form. I’d pushed up to the limit of that form, while the novel could give me so much more room to move in terms of complexity and intellectualism.

At what point did you turn to fiction?

There was a phone call from Nicole Winstanley at Penguin Canada. She said, “I’ve seen your movies, I’ve read your screenplays, and I really think you could and should write a novel. Have you thought of that?” Only for about 50 years, actually! I always thought I’d be a novelist, never a film-maker at all. My father was a journalist and a writer – I used to fall asleep to the sound of his typewriter. Our house was full of books, so the idea of writing was very normal to me. Being an author seemed a comfortable and obvious choice.

So how did you end up making films instead?

I was at Toronto University at the time, the New York underground was taking place – Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol… They were making movies on their own. It was the 60s, you know, you’d grab your camera, do your own thing. You didn’t have to go to film school, didn’t have to be part of Hollywood, you just did it! The technology of film was also intriguing. How do you get the sound to synchronize with the picture? People shoot with their iPhones and don’t event think about it because it’s automatically synchronized, but in film it isn’t. I was curious. I literally looked up “camera” and “lens” in the Encyclopædia Britannica and tried to figure out how you do all this stuff. I got a subscription to American Cinematographer Magazine. It was all very exciting, because suddenly I saw how films were made, whereas I hadn’t had a clue before.

What’s the difference between writing a screenplay and a novel?

Turning to literature wasn’t a quick switch, though to me writing has been neither obscure nor intimidating. Screenwriting is very, very different from prose writing. Most of my friends who were aspiring film-makers didn’t know how to write. I felt that I could, because I’d written some short stories that were published in university magazines and for which I even won some prizes. Screenwriting is a very bizarre, hybrid kind of writing, and you’d usually not get high marks for your style. When you get a screenplay that is very fulsome in its prose people say, “Oh God! This guy is a frustrated novelist, he should know he’s writing a screenplay.” In a screenplay you don’t describe the hero in great detail because you’d cast Tom Cruise and he doesn’t look like that. The only thing that goes directly from the screenplay to the screen is the dialogue. If you can write good dialogue, and have some sense of narrative structure, you can be a screenwriter. As for the quality of your prose, forget it! Some famous screenwriters can’t write at all – bad grammar, bad spelling, it’s pathetic! But they’re still good screenwriters. What’s more, there’s the pressure of commercial release versus art release. As time goes by, I realize that to make an unusual or a subversive film is very difficult because it’s extremely hard to find the financing for it, and this consideration comes into play when writing a screenplay.

The minute your book was out, people asked if you would adapt it to the screen. And you said no. Why?

When I directed the opera version of my movie The Fly in Paris, people said, “Obviously, you’ll be wanting screens and stuff.” And I said, “Absolutely not, I’ve made the movie, I don’t want to make it again. So no video trickery, just the complete theatrical experience. I want to do what somebody would have done a century ago doing an opera, using the music, the choreography and so on.” The same goes with the book: I didn’t write it as a template for a film, it doesn’t need a movie to validate it. Five or six producers approached me about adapting Consumed. But I just think of myself as the novelist who is quite happy to sell them the option and the rights. Give me the money and I’ll come to the première!

In fiction you can bring out certain details, like your character who notices that another pronounces “migraine” the British way.

You wouldn’t even get that in a film, or it would last a second. And the American audience wouldn’t understand that that was the English pronunciation. In fiction you can get the richness of detail. The way you can describe reality in depth is the name of the game for me, whether it’s physical, psychological or technological.

MusicCulturePhotography50Cover

MusicCulturePhotography50Cover

CulturePhotographyExhibition50Cover

CulturePhotographyExhibition50Cover

ArtDesignCultureExhibition50Cover

ArtDesignCultureExhibition50Cover

MusicCulture50Cover

MusicCulture50Cover

ArtCulturePhotographyExhibition50Cover

ArtCulturePhotographyExhibition50Cover

ArtCultureExhibition50Cover

ArtCultureExhibition50Cover

Culture50Cover#ffffff

Culture50Cover#ffffff

Culture50Cover#ffffff

Culture50Cover#ffffff

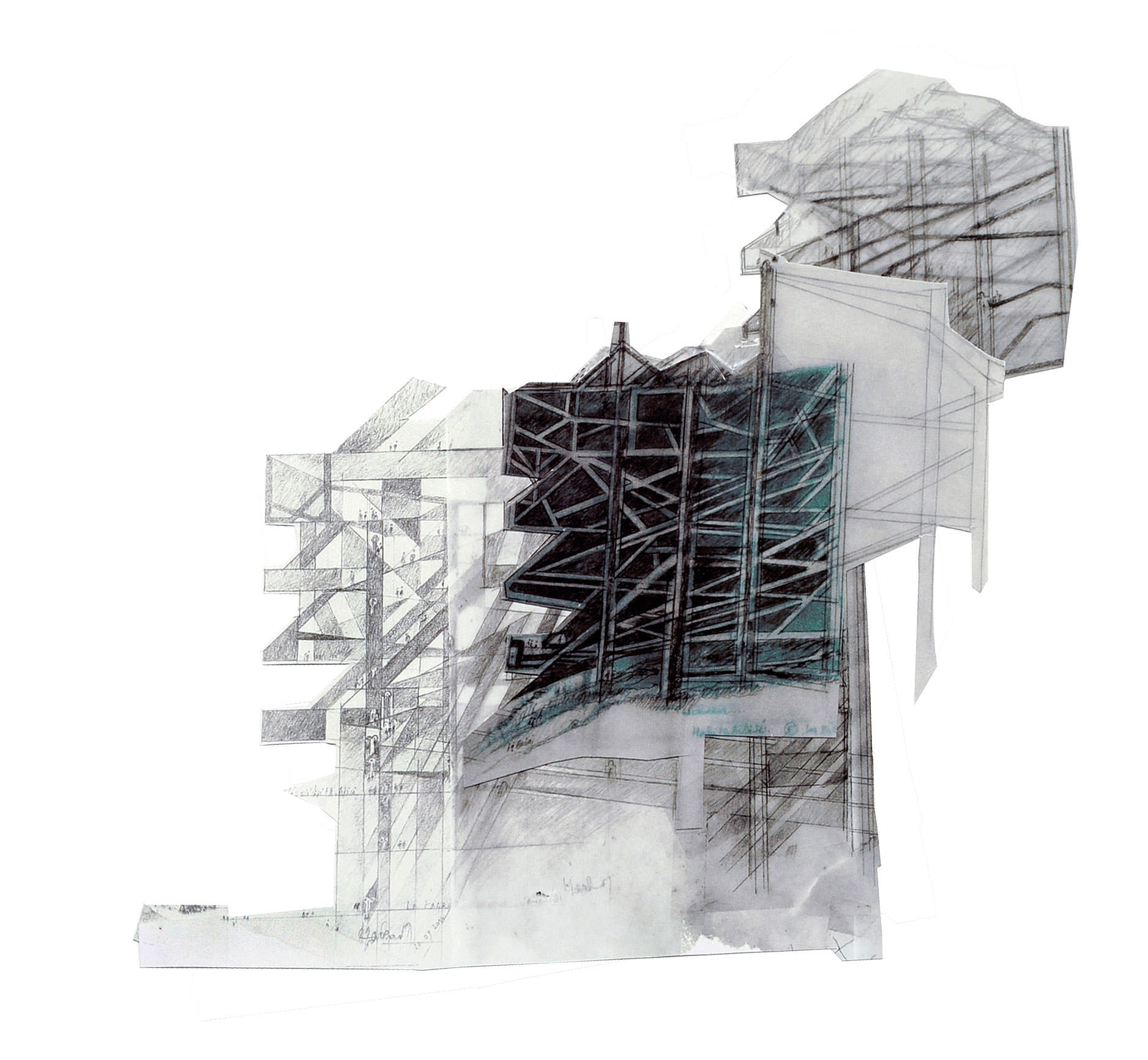

CultureExhibitionArchitecture

CultureExhibitionArchitecture

DesignCultureExhibition

DesignCultureExhibition

FashionCulture50Cover#ffffff

FashionCulture50Cover#ffffff

Culture50Cover#ffffff

Culture50Cover#ffffff

CulturePortraitMen50Cover#ffffff

CulturePortraitMen50Cover#ffffff

CulturePortrait50Cover#ffffff

CulturePortrait50Cover#ffffff

FashionCultureStyle50Cover#000000

FashionCultureStyle50Cover#000000

FashionCulture50Cover#94b2a4

FashionCulture50Cover#94b2a4

Culture50Aivbkc24Hq4Cover#edd7d7

Culture50Aivbkc24Hq4Cover#edd7d7

ArtMusicCulturePortrait50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

ArtMusicCulturePortrait50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

CulturePortrait50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

CulturePortrait50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche